Five Dwight Frye Movies (Rated From Best to Worst)

1. The Maltese Falcon (1931)

The Maltese Falcon (1931) is the first film version of the famous crime novel, but it's been overshadowed in the public consciousness by the much more famous 1941 adaptation. As a film, the '41 version is much better than the '31 version; it is much more atmospherically shot than the older version, which eschews noirish shadows for brightly lit interior sets. Humphrey Bogart is also simply a more interesting and likeable Sam Spade than Ricardo Cortez, who spends the movie leering at every woman in sight and never really seeming properly concerned with the trouble he's found himself in.

Still, there are interesting things present in the 1931 movie which make it a worthwhile watch. In the 1941 version the homosexuality of Wilmer, Joel Cairo, and Casper Gutman is strongly implied, but remains firmly in the realms of implication; it doesn't really take a genius to realize that Joel Cairo -with his scented calling-cards and Freudian affection for his walking-stick- is not straight, but the film doesn't come right out and . . . let Cairo come right out.

In the 1931 version, created before the imposition of the Hays Code, the gangsters are pretty overtly gay. In the original novel, Wilmer (the role played by Frye in this version) is referred to as "the gunsel" by Spade. This phrase, a hobo slang term derived from Yiddish, was obscure enough that it went unchallenged from his editors and was included in both the 1931 and 1941 movie versions. But while the term "gunsel" has often been assumed to mean "gunman," what it really means is "a young man kept by an elder as a (usually passive) homosexual partner."

So the hot-tempered little thug which Gutman keeps around isn't his triggerman, he's his boytoy. (Well, his boytoy and his triggerman). And the '31 movie understands the assignment; not only is Wilmer given the kind of soft-focus close-ups normally reserved for dames, but Gutman is constantly petting him possessively and stroking his face. After he flees the kitchen he's been trapped in, Spade tells Gutman, "Your boyfriend's got away." When Wilmer is ultimately betrayed by Gutman, his helpless rage is made all the more meaningful by the awareness that he's not just a gangster who's been betrayed by his boss, but a young queer man who's been betrayed by his much older partner, in a world which is deeply hostile to him. Treated with contempt by everyone around him, including the hero of the story, I'd argue that his ultimate spasm of violence is ambiguous in its intentions: is he a scorned criminal out for revenge, or an exploited outsider with no one left to turn to?

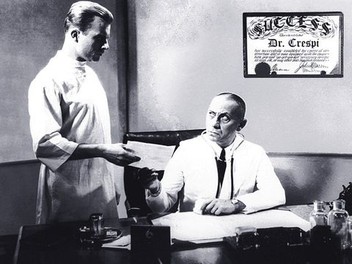

2. The Crime of Dr. Crespi (1935)

The Crime of Dr. Crespi has what I like to call a "swiss cheese plot" in that it's absolutely riddled with holes, but still manages to remain enjoyable thanks to the massive amounts of horror movie cheese inherent to a movie starring Frye and Erich von Stroheim (another cult favorite of mine).

It seems like most all of Frye's horror/crime roles fall somewhere between overtly villainous parts and pathetic ones. This movie offers a rare heroic role, but it's still tinged with the aforementioned pathetic elements. In it, Dr. Crespi (Stroheim) develops a drug which makes someone appear to be dead for 24 hours, after which they immediately revive. He uses this drug to make a romantic rival appear dead, so that he can bury the man alive and marry his wife. His assistant, Dr. Thomas (Frye) suspects that something isn't right, but Crespi beats him up and locks him in a closet. He later lets Thomas out of the closet, whereupon Thomas goes and rescues the victim from a premature grave.

I ranked this movie on the higher end despite its narrative shortcomings because it offers a glimpse at Frye in a heroic, leading role- the kind of roles that he wanted but rarely got. And like I said, it does play into the pathetic typecasting he was subjected to, but it also refutes that audience expectation in an interesting way.

See, the reason why Crespi lets Thomas out of the closet is because he thinks that he's so broken that he'll accept Crespi's mistreatment of him without protest; that he's so passive that he'll be easy to abuse and manipulate. Thomas immediately leaves and seeks help for Crespi's victim, which is the obvious correct course of action. But because Crespi (and the audience, one assumes) expects so little of Thomas, the fact that he does the logical thing becomes something heroic.